What was school like 100 years ago? A lot harder, and dirtier. Here's how kids learned in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

This Is What School Was Like 100 Years Ago

Work came before school for many children

Today’s child labor laws would be unthinkable to many American families a century ago. With the exception of professional or fairly wealthy households, parents often couldn’t make ends meet without children working the family farms, pitching in at family businesses or getting jobs in mills, mines or factories. Some of those jobs are part of the reason why the school year doesn’t start in January.

Some students rode horses to school

Louise Basse and her horse, Jane, seen here, navigated seven fields and gates to get to school in Goldendale, Washington, in the early 1900s.

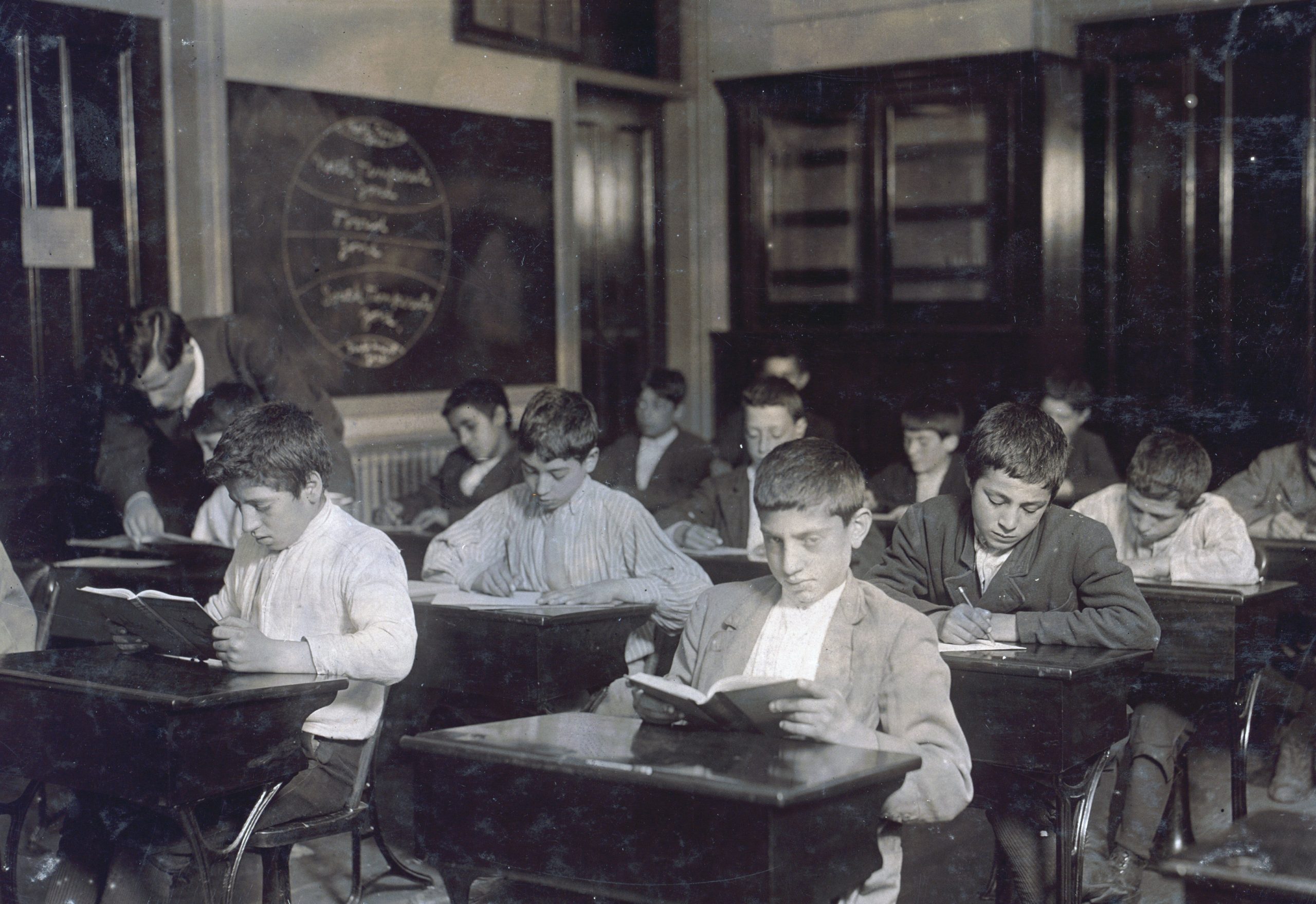

School was segregated

At the turn of the 20th century, long before the Civil Rights movement, there were limited educational opportunities for African American students. In 1910, 90% of Black Americans lived in the South, where schools were far poorer than in the North. Average school years in the South lasted only 121 days, with no attendance laws. Black teachers’ salaries were dismally low, and public secondary schools for African American students were few.

Not all children went to school

At the turn of the century, only 51% of children aged five to 19 even went to school. By 1910, the number had grown to only 59%, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Enrollment was about 20% lower for non-white students, and most only attended school for a few years to learn basic English and math. In 1900, only 11% of high school-age children were enrolled at all.

Students had specific attire that they wore to school

In 1908, Clarice Winters’ mother, Marjorie Zimmerman (back row, center), was in her last year at Bellview School in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. Fashion trends of the era often found girls wearing aprons or frocks over their dresses.

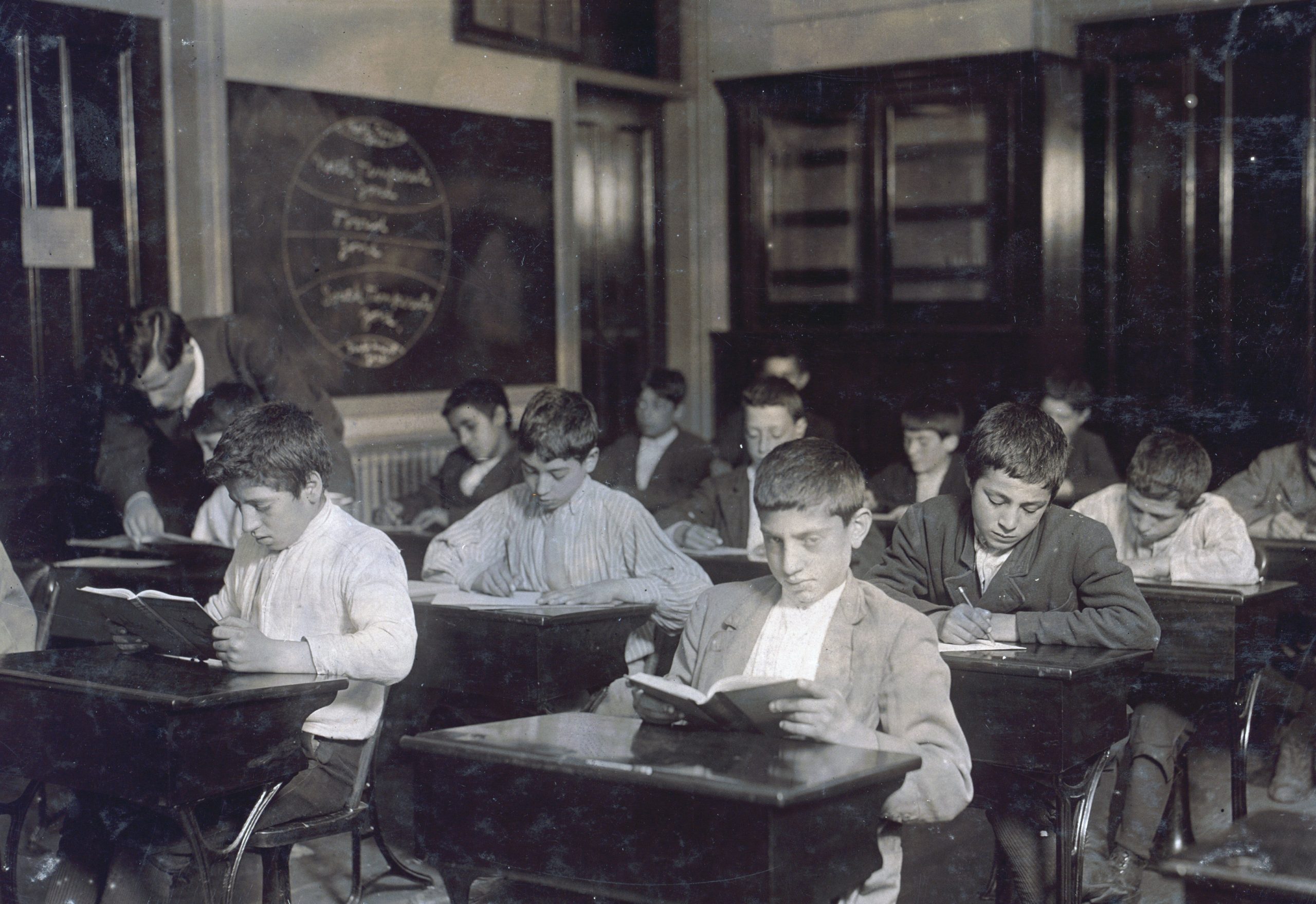

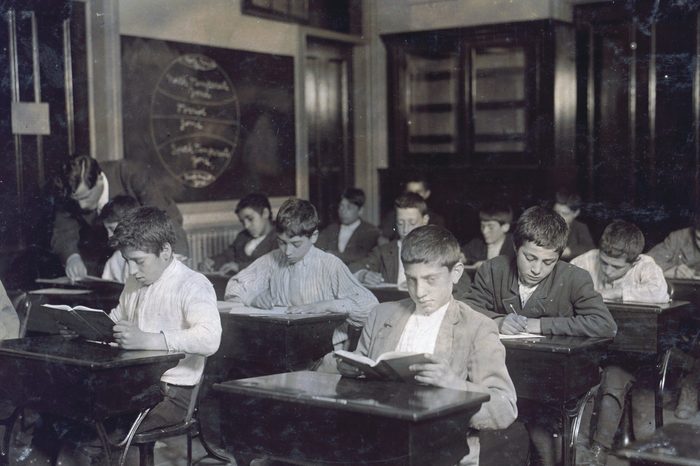

Night school wasn’t just for adults

Child labor on farms and in cities was so common in the late 1800s and early 1900s that many states passed laws requiring larger cities to provide evening elementary and high school education. One school official said at the time that parents were happy their kids could finally get a basic education without quitting the farm work or outside jobs they had during the day.

They had school sports, but the uniforms were very different

The Emlenton (Pennsylvania) High School girls’ basketball team posed in 1915 in their game attire. Ruth Nuhfer says her mother, Blanche (Grieff) Barnes, is on the right.

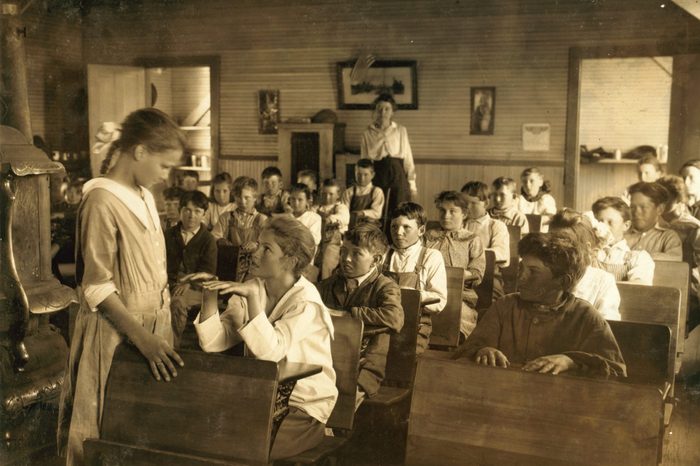

Many schools only had one room

Renata Nelesen and her brother Harold attended this one-room parochial school near Marshfield, Wisconsin, where their father was also the teacher, says Renata’s daughter, Janet Duebner of Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. He was also the church’s pastor and posed with his students for this photo in 1913.

Debate teams were more popular

Virla Jean (seated at left) was proud of her accomplishments as part of the Farmington (Michigan) High School debate team in 1929—one of many ways students found purpose and pride beyond the classroom.

Punishment was hands-on

Like today, misbehaving students 100 years ago could get detention or be suspended or expelled from school. But they were also regularly spanked, paddled, lashed or had palms or knuckles rapped with a ruler. Although corporal punishment in schools is outlawed in most of the United States today, it’s still legal in 17 states, according to the National Education Association.

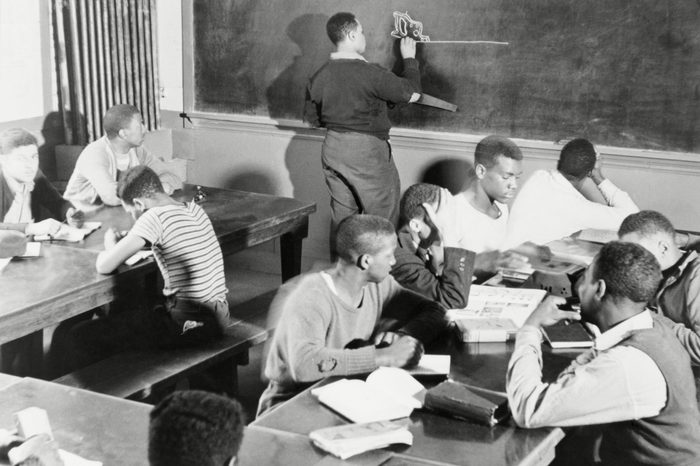

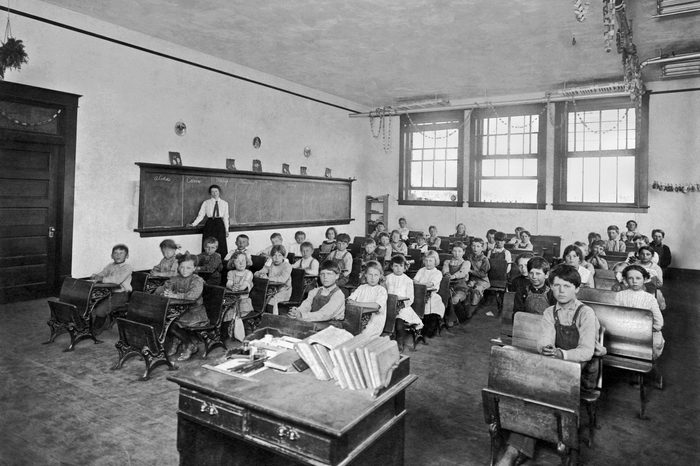

Class sizes fell in the 1920s

Class sizes in the early 1900s hovered around 35 students per teacher, on average, before falling over the next several decades. These days schools have closer to 20 or 25 students per teacher, though the numbers vary depending on factors including funding and location. Magdalene Becker started teaching in 1927 near Murry, Wisconsin. Her first class, pictured here, had 20 students.

Teachers were just as inspiring back then

Floyd Streeper (second from right) said his first-grade teacher, Miss McCune, in Onslow, Iowa, gave him a solid foundation for learning in 1929.

Many students were eager to start learning

Martha Dudley was eager to start school in 1926. That’s her little brother O.R. and sister Lillie Ruth waving in the background.

Kids just starting school were afraid to leave their parents

Alice Marks looks more relaxed in this October 1928 photo than she felt for the first two weeks of school. It was her first time being separated from Mom and Dad.

Some children really did walk 5 miles to school

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, there was no public or school transportation across most of the United States. In rural areas, children routinely walked several miles to and from school. Of course, if you had a horse or buggy, you could get there faster.

Some bus rides were long

In the 1920s, Mary Ann Kunselman (center), twin sister Martha and brother Shelton had the longest bus ride ever when they got off at the last stop.

Schools could be much smaller

Evelyn Cochran attended this school in Passport, Illinois, from 1915 to 1923. Though major cities had large schools just like they do today, one-room schoolhouses were still common in rural areas.

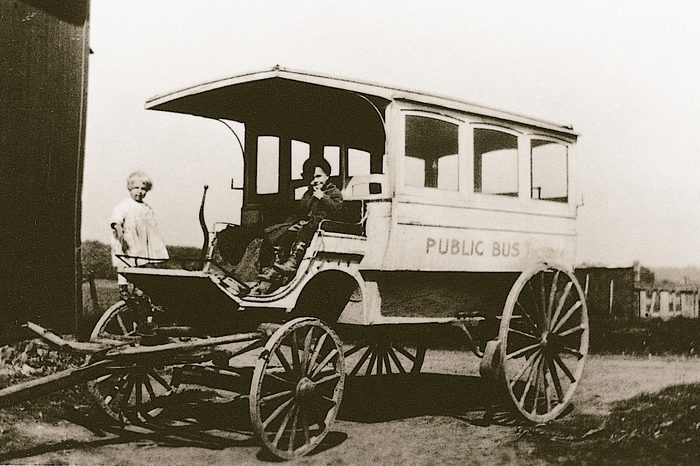

Buses used to be drawn by horses

“The horse-drawn bus was painted yellow with a door in the back. Grandpa parked it next to the barn, where kids would play in it,” recalls Elizabeth Norton. “That’s my sister Alta and brother Charles in the wagon in 1923.” Horses weren’t just used for school buses back then—they also helped deliver the mail.

Some students had their mother as their teacher

Belle Brown was Belle Barnes when she attended Edgewood School. That’s her in the lower right corner in 1924. Her mother was the teacher.

The school year was a lot shorter

Today the school year stretches from late August or September through late May or June—about nine months. In the late 1800s, kids in rural areas were in school for only five, because parents needed children to help with harvest and planting seasons. The school year got longer in the early 1900s, as educating children became required by law and more public schools were built. But farm kids were often absent in spring and fall.

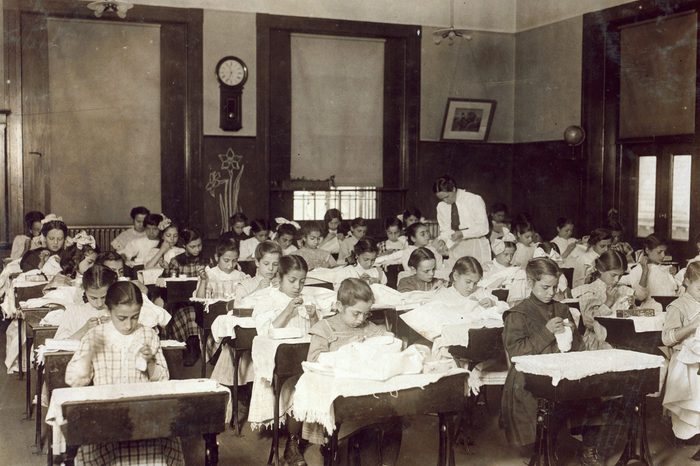

Girls learned domestic skills like sewing

Women’s charities and other groups pushed to include basic domestic skills like sewing, mending and hygiene in girls’ education. These were marketable skills and helped less affluent girls get domestic service jobs like housekeeping and laundering. Advocates of domestic education in schools also believed the skills would improve the home lives of the girls, many of whom were impoverished.

Open-air school was a thing

In the early 20th century, outdoor and open-air schools became a popular trend for children with lung disease or other health problems. The school buildings were often a tent with open sides, or just classrooms with huge windows that were left wide open, even in winter. It was thought that the sunshine and fresh air would help the kids breathe easier and feel more energetic.

Discipline was enforced

Max Philpot (front row, far left) and his buddy wondered who’d get the discipline stick first. Max did after he was caught fighting. This photo of their 1850s log school, which was later covered in siding, was taken in 1922.

Students skipped school sometimes

Willard Bailey and his friends at Inglewood High School marked their 1926 “senior skip” day with a Western twist—dressed up like cowboys and rode a wagon around town. Willard is at the top right.

Some classrooms could fit in their teacher’s car

This might be the 1923 class photo for Lucas School, a few miles south of Satanta, Kansas. It shows all the students, including Edmund Wright (left), seated in their teacher’s car.

Scissors looked the same

Using scissors is obviously what these children were waiting for in this 1922 photograph at the Presumpscot School in Portland, Maine. Ken Cole is in the last row, on the right.

Grades 1 to 8 learned together in a one-room schoolhouse

Most American kids in the 1800s and early 1900s attended one-teacher, one-room schoolhouses for first through eighth grade. Depending on the local population, there could be anywhere from a handful of students to more than 40. The youngest kids often sat in the front and the oldest in the back, though here the children are seated with the oldest on the right.

Lunch pails were actual metal pails

In the early 1900s, children’s school supplies were limited to chalk and tiny chalkboards called slates, and sometimes textbooks, according to the Library of Congress. They used slates much like notepaper and worksheets are used in elementary classrooms today—to work math problems, practice writing and spelling, and more. For lunch, children often carried their lunch in metal pails (hence the term “lunch pail”) or woven baskets.

School plays were always a hit

The art and drama department of Howell (Michigan) High School put on a production of The Wishing Well for two nights to a packed house in March 1928. Viola Stoddard (back row, sixth from right) was in the chorus.

Kindergarten wasn’t available in every town

“It was the first day of school in 1920 for me (in the hair ribbon) and my brother, Raymond,” Marjorie Leborgne says. “Raymond was 5 and going into first grade because there was no kindergarten in Kingston, New York, where we lived. I was 7 and starting third grade. Our sister Alma was 3 and too young for school. She stayed home with our mother, who is behind us.”

They had limited instruments for music class

“In 1926, I was a 12-year-old musician with the junior orchestra at Mark Twain School in Webster Groves, Missouri,” says Ione Pinsker (second row, right of the triangle). “By the time they got to me, the only instrument remaining was the viola, which I disliked, but I had promised to finish the semester on any available instrument. My real education was learning to appreciate music.”

Students put on pageants

Back in 1922, eight second-graders at McAlister School in Lawrence, Kansas, put on a pageant to celebrate Washington’s birthday. That’s James Burdette Smith at the far left in the back row.

A lot of students loved their teachers

“This 1924 picture is of my first-grade class at Warren School in Decatur, Illinois,” says Mary Smith. “I’m second from the left in the first row, and my brother, Paul, is second from the left in the second row. The teacher was Miss Pearson, whom I dearly loved.”

Teeth and fingernails were inspected for dirt

Children’s fingernails, hair, faces, and teeth were inspected for dirt, and they were taught how to properly wash up with soap and scrape the dirt from under their nails. Teachers at overcrowded urban schools also worried about contagious disease and often quarantined kids with sniffles and other symptoms.

While much has changed in the last century, one thing remains the same: The classroom continues to shape future generations, just with fewer horses and more homework.

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources

- Encyclopedia.com: “The 1910s Education: Topics In The News”

- National Education Association: “Corporal punishment in schools still legal in many states”

- National Center for Education Statistics: “120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait”

- Vanderbilt University: “Evening Schools and Child Labor in the United States, 1870-1910”

- Mental Floss: “11 Ways School Was Different in the 1800s”

- National Library of Medicine: “Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy”

- Butler University Libraries: “A Brief History of the Teaching of Home Economics in the Public Schools of the United States”

- Slate: “When Students Went to School Outside—Even in Winter”

- Library of Congress: “One-Room Schoolhouse”

- Chasing Dirt: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness by Suellen Hoy